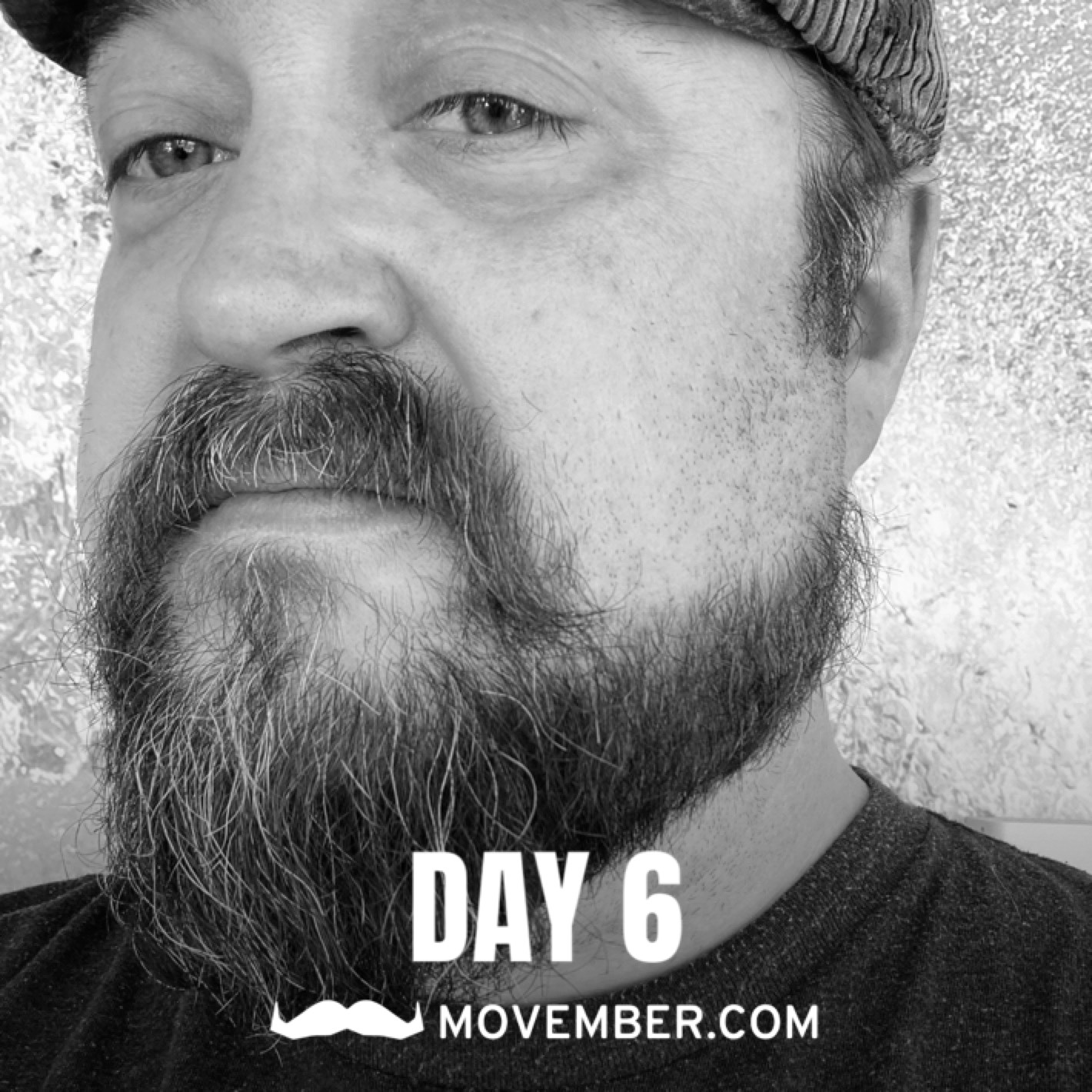

The past few years have been rough. So like the last couple of years, I’ll be mowing down into a mo. It was so fun before. Here we go again. Donate via facebook or my movember profile.

Asking all my life.

I’ve gone off the beaten track for the past couple of posts. And it’s time to get back to Ong and his characteristics of oral cultures. And today, we’re going to look at

The noetic role of heroic ‘heavy’ figures and of the bizarre

In this, Ong focuses on the tall tale.

The absurd and larger-than-life heroes and characters, in oral cultures, aren’t as grandiose as they seem. Their extreme nature is normalized & memorized over time.

It’s easy to see this in fiction, the larger-than-life images and situations we watch. With advancements in technology and CG, there is an almost infinite rabbit hole we can take ourselves.

For the longest time in our literate culture, books have held these grandiose images and stories. Then came the moving pictures. To me, it seems appropriate that some of the earliest attempts to catch our imaginations were centered around flying to the moon or robots and androids.

Most of the great stories have elements of the absurd, bizarre, larger-than-life characters and journey. They stick with you.

And not only that – they have an immediate word-of-mouth quality.

In a story with a million over-the-top moments and characters, when recounted and told to friends and family, if you miss a part, a feature, it still can captivate. The heart of the story travels, even if you don’t know exactly how big or green The Hulk is.

For fiction to be grandiose is expected. What’s really difficult to think about is what’s next: the “real” world.

In 15-20 years, what will we remember about these past few years?

It might depend on how many fictionalized movies come out.

Over the past few years, I’ve seen an interesting trend that, I think, relates to this thought – the fictionalization of history.

Take a look at these two lists, biographical films and biographical mini-series. I smashed them together to get this.

We are creating & consuming our history more and more through infotainment.

Some could argue that this isn’t real history. That these fictionalized moments are outlandish, over-the-top, made for our viewing pleasure. But maybe at the root, that’s the point. Make history bizarre, outlandish, and grandiose, and maybe we’ll actually remember a nugget of truth?

I’ll admit, my napkin numbers may be reflective more about technology. That the cost to make TV and movies is decreasing, so that overall more content is made in general.

But as I think about it, does this really sway the thought? How many books are there fictionalizing history? Is the history that we learn (not the journalistic history of historians) all but a story?

Perhaps TV & movies, by their very nature, allow for the outlandish, bizarre, dramatized life for our viewing pleasure. They are designed to recreate larger-than-life moments “on the big screen,” which is kinda why we like it.

We take in all this over-the-top content, and over time, what happens?

The absurd and outlandish fade, and the nugget of a moral, thought, or feeling remains.

Ong doesn’t oppose this outlandish and bizarre, only that in oral cultures, it was more prominent. He even mentioned that in literature, this continues. However, it’s an artifact of an oral culture. It was heavily required for an oral society as a tool to normalize information through society over time.

The “heroic” heavy figure, the Ong notes, fades with literate culture. Over time there came the “anti-hero,” that “you do not need a hero in the old sense to mobilize knowledge in story form.”

I can’t entirely agree that there was always a heavy hero. In several storytelling traditions, more complex figures took center stage. Take the trickster, the raven, the coyote, Loki, Kaulu, Mercury, the Monkey King, and more.

Let’s look at the gods of Rome or the Norse – sure, magnificent and over the top with grand powers and bizarre and otherworldly experiences – yet flawed and almost human. They were, as Ong might call them, “heavy” figures, but all heroic? No.

How about the Indigenous peoples of North America whose, for lack of a better word, gods were animals and nature itself. “Heavy” figures? Yes. Heroic? Not all.

If Ong was right about needing a hero, though I disagree, perhaps in the postliterate the “heavy” figures are not an external hero, but ourselves. Celebrities taking the limelight. While the rest stage our lives to be bigger, to be more outlandish, to be more grandiose than they are. All with the idea to be seen, and maybe what’s harder to acknowledge, to be remembered.

Though, perhaps this is a transition? Maybe we’re stewing and creating the recipe to create a new set of Roman and Norse-like gods. People who may actually have been real at one point in time, only to have their lives made bizarre and over-the-top from some sort of common societal draw.

Photo by Robert Gourley on Unsplash

Originally posted on Substack

Somewhere time slipped away on me.

Now that I’ve got a moment, it seems like the perfect catalyst to think about how time plays into our postliterate lives.

Time is one of these funny things about life. It happens, and you can’t stop it. Days, seasons, lunar cycles, life, growth, ageing, death – there is a passage of undeniable change.

Calendars are far older than literacy. And of course, it’s important to survival: knowing when winter comes, when animals migrate, when plants bloom or are edible. There is a practical application to this, and as we’ve been learning about oral cultures, when it is something more practical, it’s something worth knowing.

Though, in oral cultures, an agreement between cultures, societies and people is a far different matter. What one calls time, or how it relates, is reflective and personal. I wouldn’t expect any consensus.

As we became more literate and science flourished, we started striving for a consensus. We made rules and started focusing on smaller increments: hours, minutes, seconds. We found the solar year, calculated leap years, time zones, daylight savings time, carbon dating, relativity, space-time, and we’re finding more ways to think and make time work with what we understand of the universe.

As we shifted from an oral culture to literate culture, our beliefs and idea of time altered to microscopic moments. Like writing, time became a position in a composition of books and paragraphs, words and letters.

We called it time – but let’s face it – it’s not quite the same.

So as we get into the postliterate, perhaps the connective desire to literate-like order will fade. And in some ways, perhaps we’re seeing the cracks.

Let’s remove daylight savings.

Let’s remove time zones altogether.

Sure a stock trader, programmer, or scientist will need to care about precise “time,” but for the general population, what does it matter how close we get to “now”?

My time isn’t your time and will never be the right time, and for the average person in the average life, perhaps that’s ok.

I think our postliterate lives will be aliterate ones—lives that we know of letters and signs and sentences. There will always be some form of literacy, just cursory.

Like being aliterate, we’ll be atemporal.

We get it. We know it exists. We use a bit of it to know when to gather together for meetings or with friends & family, but other than that, what do we really need it for?

Photo by Aron Visuals on Unsplash

Originally posted on Substack

When I originally set out thinking about the social implications of orality and the postliterate world, I immediately imagined a series of old-world relationships. Ones that still exist today, though maybe overlooked or under-utilized, or ones that may have been forgotten or no longer seemed “relevant.”

Here’s an example: how we sleep.

The lightbulb changed how we slept. It changed an entire part of society, and yet, somehow, we forgot.

Another example: the washroom.

Do you remember the racks and piles of magazines and gamebooks in the washroom? I have a few friends who have a couple of books still in the washroom – but between you and me, I think it’s more for decor and homage to their childhood than actual purpose. The iPhone altered what we did in there.

What have other aspects of everyday life been lost over time as we’ve introduced technology?

As we slide into the postliterate, my thinking is that those lost and forgotten pre-Gutenberg aspects and social structures might creep back into our lives. Imagine if, one day, light bulbs and phones stopped working. My feeling is we would start segmenting our sleep again and bringing back the washroom library.

So come with me and try to think of how society has changed between now and 1450, now further to the year 1000, 0, 100BCE, 1000BCE.

Like I do with my series of Ong’s characteristics of oral society, I’ll start throwing these thoughts out here as we go.

The very first is what I call:

This is a good first step in taking our minds to imagine what life might be like. It’s a relationship that we are all aware of. We call it different things depending on context and industry: student, resident, associate, apprentice, mentee. They may be formal or informal relationships.

Lawyers, Doctors, Artisans, and Trades have formally kept this tradition going and know how vital it is. These industries, and others that follow this process, are aware of a simple truth that our literate-dominated world sometimes forgets.

It’s not just information, but its application, the feeling of it, that is required for understanding, of knowledge.

The written word has detached the emotion and persona of those with knowledge. Imagine reading a manual about anything. Learning from literature alone is learning alone. It is your own voice in your own mind. It’s your own body imagining actions & movements performed.

What orality brings to a lesson, or thought, is the deep-rooted understanding that while you may not remember who said it – you remember it was someone else. Not you. And in that understanding come reverence and respect for the path of information. For the path of history. It’s not just off-hand recognition of Mastery, but the emotional understanding of where it came from.

I’ve been building up to this idea that we won’t be “illiterate.” I think it will be more likely aliterate. We will still be inundated with information. Though, we might not care.

Yet, remember the literaty from a couple of weeks ago?

In our past, the Master has been the gatekeeper to knowledge and information. The image of the elder confounding the student with seemingly irrelevant tasks and exercises. Then came literacy, and the Master, still with irrelevant tasks, became the librarian with hordes of ancient texts piled high around them. Both of these images are intertwined with experience and age.

The challenge we’ve faced with Masters is that technology has shifted the control of information by reducing the cost to produce and distribute to almost free. It has made the time to gain information irrelevant. The speed of language has allowed the young to garner just as much information. What’s worse is that computers can even assimilate it faster than anyone.

And here’s where we’re starting to see the crack of information alone.

The new Master is beyond data alone. New Masters, regardless of age, are arising as those that filter and navigate the infinite for answers. They use it as a foundation to gain insight, filter between folklore and truth, navigate and come out of the other end with true mastery. They are the embodiment of passion and drive for their industry and craft.

Master Penman Jake Weidmann youngest of his kind; one of twelve existing today. In an act that was once standard, penmanship is no longer has a permanent place in school. It’s more a fascinating divergent lesson. A few chapters might be dedicated to the strange cursive writing style – pre-QWERTY.

Weidmann persisted. He uncovered and hunted for old techniques and then tried them himself. Filtering through fact and fiction for himself.

Lars Andersen an archer and disputed Master who is trying to navigate between fact and fiction of ancient methods in his craft. Is his underhand style new or re-invented? Some even dispute the materials he cites as his inspiration. They are hidden in legends and paintings. Yet, his mastery cannot be denied no matter how disputed. It is faster than anything seen. Unlike the tried and tested mastery of Jake, Lars’ path is more obscure to uncover.

What would it be like to have someone with this drive for mastery as a teacher?

I think it’s understood that we’ve got a feeling that education needs change. The recent pandemic is challenging education even more. What to change, how to change?

Modern standardized tests turn children into widgets. Read book A, then book B. Put this piece with that and carry them down the conveyor belt. Spit them out like a new car. Products of industrialized education. Like the printed word in a press. Lather with ink, hang to dry and put it on a shelf to sell.

It’s more complicated, I’m sure.

Since the early 1900’s methods like Montessori, Waldorf, or democratic schools like Summerhill have for over a century tried to show our industrialized printing press method can’t work.

My feeling is that we have a sense of why our education system is challenged. In start-up terminology, we have an issue of “scale.” I think we know that the master-apprentice relationship is the best, that one on one individual attention and care is best – but the cost of one on one grows considerably as the system grows.

As orality continues to retake hold, perhaps solutions will become clearer. Perhaps we’ll see a larger influx of children taking on their parent’s trade or specializations starting sooner when a Master sees a child’s inclinations and invites them to join their school (would we go so far as a sorting hat?). Making more, and smaller more specialized schools. Broadening the scope of what a successful education looks like and achieves.

And here is the next logical step from The Master & The Student. Where do they learn? Where did they learn? How do they continue to learn?

What used to be the institutions that supported the Master & Apprentice? Are there any that haven’t held well over time? Guilds?

But that’s for another day.

Photo by jose aljovin on Unsplash

Originally posted on Substack

Between the years 550 and 700, something interesting happened. With the fall of Rome, we stopped speaking and using Latin. What’s more, languages shifted and mutated in various parts of the world and by 700 the common person couldn’t speak it, nor did they have anyone in their lives that had any memory of it spoken. It was mostly dead.

Yet – one of the secret societies kept this language flourishing. Schools.1

The knowledge amassed by the Roman Empire was so substantial, that to learn anything of substance, it was written in Latin. Schools really had no choice. And what a better way to keep it than to use it. But, outside their walls, there was no longer any particular use. It was a language for a single purpose – education.

I doubt anyone can argue against the bonds created through language. They become deep and “societal” in nature.

Those that can speak Dothraki or Klingon; those First Nations that are working to keep their culture alive through language; those that program in C, Ruby, Python, PHP, etc…; those that can sign; those that… well I can keep going on.

I also doubt that anyone in the world is exempt from that “outsider” feeling when you are surrounded by a language you don’t understand. It’s humbling.

There’s a definitive line that’s made through the marriage of skill and culture.

Did this Latin-only secret society, more than a millennia ago, help consolidate and foster today’s scientific community?

How language and the written word have built the academic community is an interesting thought. The cornerstone of dialogue is the “publication” of knowledge. The heated debate, arduous experimentation, visionary purpose comes down to the printing press. That’s, however, for later thought.

What I’m thinking of here – is in the language itself. The Latin that still exists, knowing its Latin name/form can define a guild of sorts. No different than knowing what a GIT repository is, or a P-trap, or an Octonion.

However, this isn’t anything new.

Some choose to learn, and some choose not to. But what if no one “cares” to learn anymore?

Perhaps calling them The Literaty is a bit extreme, but I feel appropriate.

Remember that side note from last week? That 15%? That’s important.

As we carry down the path into the postliterate, my belief is we will never become illiterate. We can’t ever go back. There will always be “stop” signs. There will always be light touches of language. Summaries to read: Coles, Cliff, Blinkist.

But the choice to go deeper into the written word, to read the truly complex, or just flat out long books. That’s what forms a new group.

The marriage of skill and culture. Those that choose to create and consume long-form content. The mix of skill and culture.

That 15%. They will walk among us knowing that outside of their walls – no one does it.

Photo by Frantzou Fleurine on Unsplash

Originally posted on Substack

It’s time for the next review of one of Ong’s characteristics of an Oral culture.

At the heart of it, Oral cultures avoid subordinate thought. There is no real order per se but a series of “and”s.

Joe went to sleep. And Joe plowed his field. And Joe drank a cup of coffee. And Joe ate dinner. And Joe walked to the store.

What order was any of that?

To an oral culture – does it really matter?

Based on A.R. Lauria’s Cognitive Development, it could be based on an oral mind’s ability to deduce and infer. Without relevant experience, it refuses the question. Here is one of many examples they posed to oral people:

All precious metals do not rust. Gold is a precious metal. Does it rust or not?

What the study founds was pretty fascinating. Out of those without any relevant experience, most (85%) were unable to or flat out wouldn’t solve the question posed. They didn’t care, thought the question was stupid or was dumbfounded why anyone would ask. It made had no relevance to them and their situation.

Of people who did have some experience, for example, had seen a piece of gold, they didn’t solve the questions by a landslide, only 60%. There were still subjects that refused. Only after being given additional, conditional assumptions of practical situations would the others, with experience, solve the question posed.

Interesting side note: Back to the group surveyed without any experience. Did you do the math? Not everyone refused. 15% could work through the inference without help. Perhaps this is nature? Perhaps this is the spice of life? Take a read through Who moved my cheese?

In Amusing Ourselves to Death, Neil Postman brought up the “And now this…” culture. One that is ok with non-linear experiences. The phrase taken from newscasts outlines our new ability to detach from linear experiences. To switch seamlessly from graphic violence to a feel-good comedy without missing a beat. All it takes is a click of the button, and voila, new feelings.

Today we have additive experiences every day. When you find a new blog, do you start at the beginning? Facebook posts, tweets, grams, snaps, stream after stream, is there a semblance of order or hierarchy to them? No.

What’s more interesting is in some of these “streams” of additive moments, they remove any sequential nature – with algorithms bringing to the forefront popular posts from friends weeks ago folded into the present.

Now, what about binge-watching? That’s linear. Right? There may be a linear and subordinate nature to it, but only in the show itself. What about the context of the world? Where you are in your own experience might not be aligned with your friends. We have learned to remove expectations or assumptions of order onto others – they may be ahead or behind.

And because we can no longer have any expectation of order, we treat each other as beings of additive experiences.

Jeff ate dinner. And Jeff watched Game of Thrones. And Jeff shared his pictures at the park. And Jeff tweeted that meme. And Jeff texted Joe. And Jeff slept.

What order was any of that?

Does it really matter?

Originally posted on Substack

More of Ong’s characteristics of an oral society.

“[O]ral societies live very much in a present which keeps itself in equilibrium or homeostasis by sloughing off memories which no longer have present relevance.”

Have you wondered why it’s taken humanity so long to progress?

Unless it has a practical function, most oral people will defy further thought1.

It may have been systemic or practical to slough memories off. The effort required to learn and keep useless knowledge takes away from survival: from plowing and planting, from hunting or being hunted, from preparing and planning the long winter.

But now – we slough for different reasons. It’s easier.

“Oh – what was that movie with so and so that had that guy with the horse?” IMDB.com.

“Hey, Google, what does a whale sound like?”

The amount of input we are taking in is too much. The amount of information is piling and piling on top of us all. Add to that, the amount of information we need to sift to find the relevant information. Or the information to inform us if the information we used to find the information is real information? Get it?

No wonder we slough.

However, in offloading, Ong highlights an equilibrium that happens. We become more like our peers and wish things to stay the same. Ask google what homeostasis means.

Let me start by saying I’m not happy with some areas that this idea can go. Here lays a pile of darkness on fire on my doorstep. And I feel it’s easy to stomp right into it. But I’m going to choose not to. You can stop reading here and go there on your own. There’s enough out there I’m sure.

So instead I’m going to talk about a possibility I hope for, given we’re not the same as we were.

What is similar?

If we are moving into the postliterate and our oral sensibilities are coming back and, if Orality doesn’t generalize and, if Orality is fluid, let me ask again.

What is similar?

Please let it be something else. I want the postliterate idea of this to change with all the options of so many beautiful and diverse commonalities.

I don’t want homeo-algorithms creating systems that funnel us, and label us and lead us into similar ideologies and views. I don’t want my internet to be different than your internet. Yet, with the mountain of “sloughing,” programmers and companies feel like they have no other choice to get us what we “want.”

Instead, let’s go back and think of this:

All of them are Romans. Rome had so much diversity. Heck, they were polytheistic! “A pantheon of gods and goddesses, along with their own religions and rituals.2”

It stands to reason that they were kinda cool with not all believing in the same thing, or looking the same way. And at the same time, they were all Romans.

Read Who Moved My Cheese. On a good day, most of us don’t like change. There’s a preference for staying with what works.

And yet, given that we have gone through a boom of change over the past 500 years like no other.

But I’ve always had a problem with the idea that this growth we’re in is sustainable. We have the audacity to believe that we are capable of exponential growth in perpetuity. And yet every night we go to sleep. Night comes. Winter comes. Rest is required for life.

I think this pandemic has opened our eyes to this. And funny how out of all of this, slowly recovering, the internet is a buzz on “social audio.”

An oral culture requires our mouths to rest. Our minds to rest. To consume the words from someone else. Oral cultures take their time. They stand still. They prefer it.

Perhaps this is where AI and the future of offloading onto technology open new ways of being. Is our postliterate future one where we learn to stand still – but in a self-driving car?

The thing about homeostasis is it’s a process that wants stability in a system for survival. Nowhere does that mean it’s opposed to change. Ong chose his words well. When things are good – sure, things slow down. Yet it’s also fast to find new stability and adapt. 200 years is all it took after the fall of Rome to fracture into so many different languages.

Change isn’t easy. Imagine water becoming gas. In flux, the change looks dramatic and violent. And, I think, we’re metaphorically deep in a boiling time. Hopefully, our oral sensibilities are what will help us adapt and find the right equilibrium on the other side.

I have yet to read it, but a previous professor of mine gave me an intriguing summary of Douglas Biber’s Variation across speech and writing. He paraphrased “when we have lots of time, we tend to develop texts that are prose-like; when we don’t, we tend to develop texts that are speech-like, without respect to whether the text is written or spoken.”

When we have the cognitive wherewithal we take it. When we don’t we scream “look out!” And perhaps that’s where we are in our transition?

If was McLuhan is right in the 60’s when he said we were already into this new era, perhaps we’re only about 70 years into this postliterate transition.

130 years left to go to see how we adapt.

Originally posted on Substack

In the world of ecology, things are never the same, only evolving. In my intro to this project, I talked about the story of the wolves of Yosemite. 14 wolves had amazingly positive results, but is Yosemite’s ecology the exact same as it was before everything when south? No. It can never be.

And this is the underlining principle of – once you go literate, orality is gone forever. You can never go back. All the thought leaders are conscientious when they use “orality” after the written word. They get very intricate in their choices of words and phrases: primal orality, oral sensibilities, oral residue, postliterate.

Lately, in my mind, I’ve begun to think about orality and literacy in a geological sense. Imagine Orality and Literacy in an ever-evolving process of erosion and sedimentation. Mixing to make different forms. Never again the original form. Requiring a lot of time and energy to mutate.

So, of course, it’s not orality, in the truest sense. The academics are spot on to avoid the word. On the other side, my non-academic says – stop your fancy words! It’s a rock.

To the laymen, it’s a rock, a cloud, a tree. For the masses to truly take on a concept, I feel we need a generic “word.” For all the colours of the rainbow, the average person still can say red, blue, green. I want orality to have the same understanding.

However…. this is where my literate mind starts having a small temper tantrum.

I’ve been struggling with an interesting and challenging thought. In purest orality, in what I’ve been reading, there are no generalizations. The ability to create a group of “X” goes out the window.

Everything has a unique and contextual quality void of the need for broad strokes. It’s no wonder why we wonder why there seem to be countless names of the same animal in different phases of life, why there could be 12 words for rain or snow in some cultures. It may be because, in an oral culture, it was unique and required a name unto itself, specific for the context.

And with this in mind, dialects and the history of language variations start to make a bit more sense.

In my pride of pattern recognition, when I create a view of my world, it’s worse than never the same again, it was never all the same in the first place.

Simply put, fragmentation. More fragmentation in meaning. More fragmentation in thought. Worse yet, overlapping and unrelated fragmentation of the same things. Different intent and “meaning” for the same thing.

As technology has been advancing, I think some of this fragmentation is occurring naturally. We’re losing our ability to put things into buckets. It’s dividing and amalgamating— erosion and sedimentation. Here are a few examples:

Bye-bye generalizations. What’s more interesting is your Youtube might not be my Youtube. Now imagine that for everyday words like “bank,” or “book,” or “spoke.” The same word – different connotations with unique contextual awareness for each.

I imagine the fragmentation is going to increase. But unlike previous geographical divisions, it will be a reflection of our community, or probably more like an amalgamation of communities, within this global village.

Here’s one last example you need to ponder and maybe ask your friends:

Question: What book did you last read?

Question 2: Did you actually “read” it, or was it an audiobook?

Photo by Matthew Kosloski on Unsplash

Originally posted on Substack

This has been a tough question for me. After all, if I can’t answer this, then to put it lightly, what’s the point?

And then, when talking it out with someone recently, I made a connection.

It’s been a couple of weeks, and the chaos that we watched in the United States seems to be dissipating. However, there is still a vast divide that needs to be overcome.

I’ve brought up Ong and the Cognitive Development study – and at the root, if our oral sensibilities are increasing – the fundamentals of logic change. And if the fundamentals change, the rules of debate change.

And if you have someone with more literate sensibilities arguing with someone with oral sensibilities? You might as well be speaking a different language. Until we learn what these real differences are, everyone will be yelling into deaf ears on either side.

I bring up the United States because I wonder if that’s at play in some part of the conflict. Two groups with drastically different sets of rules of debate. The arguments are incomprehensible by the opposition.

There’s this phrase that I keep hearing over and over, “Yes, but this is new!” In some sense, sure. But in a lot of senses, I don’t think so.

What I’m wondering is, is this a coming of age story? Are the arrogant teenagers of countries simply taking a step closer to understanding our elders in terms of societies and culture? Putting on suites to go into the world’s workforce and making adult decisions with all the nuances and complexities that only an older society could comprehend.

I feel it when I leave North America ( Canada for me ). The moment I land in Heathrow, the land, the culture, the cities feel “older” than mine. History seeps out from the walls. No matter how new-aged or foreign, there’s a sense of history for me. And maybe this history comes from these times older than I can comprehend.

And perhaps with the age of civilization, there is more diversity in sensibilities, oral, literate, other? Or perhaps more relevant examples of when their country was oral? After all, in our “western” history, our North American “countries” have never experienced this, because after all – they didn’t exist in the post-classical ( 400-1500 BCE ) hay day that the rest of the world has.

My point is, just like teenagers and adults do – we fight over the plight of something new and something old. Throw away what our elders know to only come around in the end and realize both are right.

So if all of this battle is a coming of age, then there are rules to how. And in understanding oral cultures before we will take that step to a solution. I suggest that we all brush off our communication skills in “rhetoric” – you do have those, right? 😬

You may have noticed that I posed the subtitle as a question – not a statement. It wasn’t a typo.

While I feel we should brush up and learn more pre-medieval rhetoric – there is also what I think maybe a gap in history, and I’m starting to look to learn more about it—that of the commoner.

The printing press lowered the barrier of entry into literacy and the written word. Before then, however, it was incredibly high. So high that only a percentage of a percent had access or the wherewithal to be trained or hire trained people. And so what we really know might be skewed to the elite. We have movies about Royalty and knights, about emperors or “previous” lords cast into slavery – but what do we really know about the common man, woman, or child? What persuaded the peasants, serfs, or the freemen in medieval times? What do we know about their sense of debate and logic? How did they debate and come to a common-sense amongst themselves?

I remembered once being told that while we can make many assumptions and inferences from Shakespearan times, like what the common population was interested in being entertained by, we actually know very little. It wasn’t a real representation of the masses. In sad honesty, it didn’t matter: fear, torment and survival were.

I hope that’s not where we go again. I hope we get through this postliterate hiccup all intact. If I have a nugget of a provable theory here, there’s some bit of insight into this literacy/orality division that once was.

Originally posted on Substack