I’ve been digging into a thought for the past week starring out into the void wondering what to do next.

With Decentralized/Federated Social Media, I’m seeing a lot of discussions on how do we want to run ourselves? Ethical, rights, power and other conversations all around and to do with Governance.

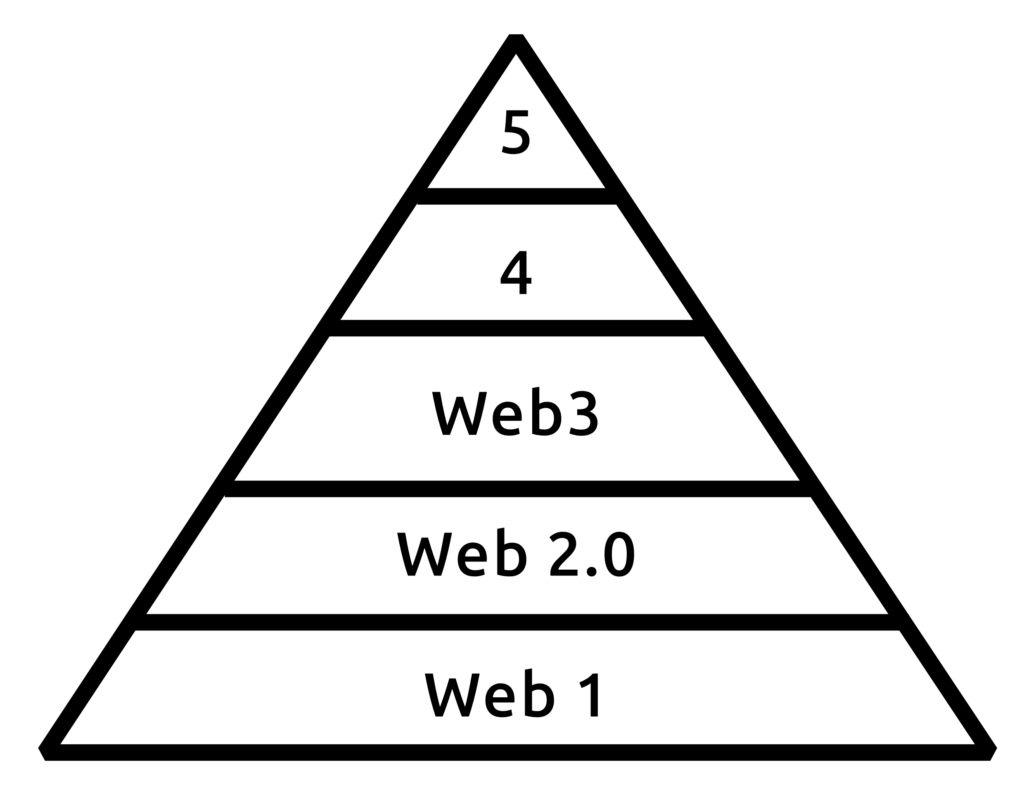

Before I do continue, here’s something I use as my framework

My Web Pyramid

Like Maslow’s Pyramid, here’s how I picture the evolution of the web.

Web 1 – Media (publishing)

Web 2 – Communication* (2 way communication)

Web 3 – Economies

Web 4 – Governance

Web 5 – Citizenship

And like Maslow’s theory, these layers aren’t independent, and we are always in flux as we go up and down depending on social need.

* Update: I previously have called Web 2 “Community”, but I’m rejigging that thought a bit.

Decentralized?

Could this pyramid be more about a decentralized, autonomous, or independent web? Could this be about scale and accessibility? 🤷

Not just the ability to publish, but at an economical scale that it’s easy and cheap for one to publish. Just like it’s easy to discuss, or now… make your own digital currency.

The structures of Governance

I’ve started investigating several types of governance. Smart Contracts, Decentralized Autonomous Organizations (DAOs), Coops/Unions/Guilds. There are so many ways we’ve governed ourselves.

Here’s a nice summary of options in 2 parts:

Tech to help?

One of the cons in all of governance is the time and effort. And that’s where I’m curious about the tech that could help. Where could it help? But some of these are it’s tricky and at scale costly.

- AI

- Summarize all the legalese

- Get updates to legislation

- Keep everyone aligned

- Ask for advise and next steps

- Seek feedback from

- Decentralized and transparent ( open )

- polling and decision making

- identity (this one is not really a can we… it’s more like which methods)

- law & legislation management

Creative Commons but for governance

Creative Commons helps me understand copyright in a way that made it accessible. It gave me tools and options I never thought of. Governance feel the same in a way.

- Where does one start?

- What are the options?

- How do I pick methods and models?

- Can I cherry pick or modify?

- Is there a common resource option to discuss

- Can we make it a bit more relatable?

What it all means with Orality

As we shift into an aliterate world we’re going to need to all understand governance a lot more.

When England reached a literate tipping point ( 50% ) the monarchy changed dramatically. At the time of the formation of The United States it was most literate societies on the planet.

Our governance will shift dramatically again. It’s time we have a good foundation or understanding when it does.